Architecture has always been a tool to express authority and influence. From ancient pyramids symbolizing divine kingship to modern skyscrapers showcasing economic power, buildings communicate dominance, wealth, and control. Here's what you need to know:

- Ancient Civilizations: Structures like the Great Pyramids of Giza and the Terracotta Army asserted rulers' control and divine status.

- Medieval Europe: Cathedrals and castles reinforced religious and feudal hierarchies.

- Modern Era: Skyscrapers, government buildings, and urban planning reflect state and corporate power.

- Design Elements: Scale, material choices, and city layouts enforce hierarchies and access.

- Shifting Focus: Today, architects are rethinking their role, prioritizing community needs and ethical practices.

Architecture shapes societies not just by reflecting power but by actively reinforcing it. By learning from history, modern design aims to balance power and serve broader societal goals.

Historical Periods: Architecture as Power Symbol

Ancient Civilizations: Monumental Authority

Throughout history, ancient civilizations used architecture not just to serve practical needs but to project power and authority. These monumental structures were crafted to inspire awe, symbolizing the divine or political dominance of their creators.

Take the Great Pyramids of Giza, for example. Built by Pharaohs Menkaure, Khafre, and Khufu, these towering structures dominated the Egyptian landscape. They were more than tombs; they were statements of divine kingship, asserting the pharaohs' god-like status and their control over vast resources. Their sheer scale ensured they remained unmatched symbols of power, visible for miles.

In Mesopotamia, the Ziggurat of Ur (circa 2100 BCE) served as a striking symbol of the connection between heaven and earth. These stepped pyramids reinforced the king's role as a bridge between the divine and human realms, blending religious significance with political authority.

The Akkadian Empire took a different route with the Victory Stele of Naram-Sin. This artifact commemorates a military triumph, depicting Naram-Sin as a towering, god-like figure. The hieratic scale and imagery of him defeating his enemies sent a clear message: the ruler's power was absolute.

China's Terracotta Army, built for Emperor Qin Shi Huangdi, showcased authority through its immense scale and precision. Thousands of life-size terracotta soldiers, horses, and chariots were arranged to mirror the urban layout of the capital city. This massive undertaking symbolized the emperor's control over life and death, ensuring his dominion extended into the afterlife.

These early examples reveal how architecture became a tool to assert dominance, laying the groundwork for how power would be expressed in later eras.

Medieval and Renaissance Europe: Religious and Feudal Control

During medieval Europe, architecture became a reflection of both religious and feudal power. The Catholic Church, a dominant force in this period, used grand cathedrals to demonstrate its influence. These towering structures were not only places of worship but also symbols of divine authority and immense wealth.

Feudalism, the backbone of medieval society, was physically manifested in the landscape. Castles, often perched on elevated terrain, were clear markers of military and political dominance, reinforcing the hierarchical structure of land ownership and service.

As trade revived, cities and city-states flourished, bringing new architectural expressions. Monarchies in England, France, and the Iberian Peninsula began to assert their power through distinctive styles, reflecting their growing influence. Religious fervor during this time spurred pilgrimages and the construction of monumental cathedrals, which served as both spiritual centers and symbols of collective identity. Their construction required vast resources and labor, showcasing the Church's ability to mobilize entire communities.

The feudal system, which shaped much of European society from the 9th to the 15th centuries, left its mark on the architectural landscape. The eventual abolition of feudalism, such as in France on August 4, 1789, marked a dramatic societal shift. As the French National Assembly declared, "The National Assembly abolishes the feudal system entirely," signaling a new era of equality and change.

Modern and Contemporary Power Structures

Architecture's role as a symbol of authority didn't end with history; it evolved alongside modern technologies and societal shifts. Today, buildings continue to reflect power in new and innovative ways, shaping how we experience and interact with the built environment.

Government buildings remain symbols of state power, while corporate skyscrapers now dominate urban skylines, representing economic influence. The Burj Khalifa in the UAE, designed by Adrian Smith of Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, stands as the tallest building in the world. Completed in 2010, its sleek design incorporates Islamic architectural elements, blending cultural heritage with a display of national prestige and economic ambition.

Modern architecture also embraces cutting-edge technology and sustainability. Frank Gehry's Guggenheim Museum Bilbao, with its flowing titanium form, redefined contemporary design, while Zaha Hadid's Heydar Aliyev Center in Azerbaijan uses parametric design to create a structure with no visible sharp angles. Similarly, Apple Park, designed by Foster + Partners in 2017, combines futuristic aesthetics with eco-conscious design. This $5 billion circular campus reflects corporate values and technological sophistication.

Architecture also intersects with technology in less visible ways. For instance, China's extensive surveillance network, with over 700 million cameras, represents a modern fusion of design and control.

Yet, architecture isn't solely about asserting authority - it can also challenge it. Projects like San Francisco's Park(ing) initiative transform unused urban spaces into temporary parks, encouraging community engagement. Similarly, the Teeter-Totter Wall at the US/Mexico border uses seesaws to connect children on either side, offering a playful yet poignant commentary on division and unity.

As Patrik Schumacher aptly noted, "Architecture always carries a societal agenda. It sets the stage for the reproduction of social life and channels communication and interaction in subtle but powerful ways". This dual nature of architecture - as both a tool of control and a medium for liberation - remains central to its impact today.

The influence of architecture on social equity is undeniable. Studies reveal that up to 60% of health outcomes are determined by zip code alone, with household incomes in segregated white neighborhoods nearly doubling those in segregated communities of color. Life expectancy can even differ by four years based on location. These statistics underscore how urban planning and architectural choices continue to shape societal dynamics, either reinforcing or challenging existing power structures.

Architecture of Power: What the Built Environment is Trying To Tell You

Design Elements That Show Social Power

Architecture has long been a silent yet powerful storyteller, conveying authority, wealth, and hierarchy through its design, materials, and spatial arrangements. Every detail, from towering structures to luxurious materials, serves as a statement of influence and control.

Symbols in Design and Scale

One of the clearest ways architecture asserts power is through scale and grandeur. Across history, massive structures have been built to inspire awe and demonstrate the resources of those in charge. Take the Colosseum in Rome, for instance. Built between 70–80 AD under Emperor Vespasian, it could hold over 50,000 spectators. Beyond entertainment, it was a bold display of imperial dominance.

Material choices also play a key role in signaling status. The Taj Mahal, completed in 1653 under Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan, is a prime example. Its gleaming white marble and intricate inlays were not just artistic choices - they reflected the immense wealth and political strength of the Mughal Empire.

Symbolism in architecture often adapts to political and cultural contexts. During British colonial rule, Lutyens' Delhi was designed with grand avenues and imposing government buildings, blending Western and Mughal styles. This fusion was a calculated move to project colonial dominance while acknowledging local aesthetics.

On a more authoritarian note, the Nuremberg Rally Grounds showcased rigid symmetry and monumental scale to represent control and discipline. The geometric precision of these structures mirrored the regime's vision of absolute authority.

But architecture’s influence doesn’t stop at individual monuments - it extends into the very layout of cities.

City Planning and Space Division

Urban planning is a subtle yet potent tool for reinforcing societal hierarchies. The way cities are organized - where people live, work, and gather - reflects and perpetuates power dynamics. Spatial hierarchy, or the deliberate arrangement of spaces, communicates status while optimizing functionality.

History offers stark examples of how city planning has upheld inequality. In the United States, practices like redlining systematically denied loans and services to predominantly Black neighborhoods. This not only stifled economic mobility but also entrenched patterns of segregation that persist today.

“Planning is the government’s tactic to direct society under its dominance,” Moghadam and Rafieian observe.

City layouts often place government buildings in prominent areas while relegating service facilities to less desirable locations. This spatial organization sends a clear signal about which roles - and, by extension, which people - are deemed most important.

Even today, zoning and land use decisions continue to influence resource distribution. These choices shape access to quality schools, healthcare, and jobs. For instance, in Australia, where over three-quarters of the population lives in urban areas, such planning decisions have a profound impact on daily life.

This division of space also highlights distinctions between public and private realms.

Public vs. Private Spaces

The line between public and private spaces reveals much about power dynamics. Public architecture, funded by governments, is meant to serve the community, offering accessibility and shared utility. On the other hand, private architecture caters to individual or corporate interests, often emphasizing exclusivity and personal expression.

Design choices subtly indicate priorities. Features like grand staircases or secluded entrances can signal who is welcome and who is not. Public spaces often include barriers - fences, "no sitting" signs, or private security - that regulate behavior and limit access.

Communal spaces bridge the gap between public and private realms. These shared areas, such as community kitchens, gardens, or childcare facilities, foster connections and a sense of belonging. For instance, some public housing projects in Vienna incorporate communal spaces to strengthen community ties .

Control over space - whether through access, design, or usage - acts as a form of social regulation. While private spaces emphasize exclusivity, well-thought-out public and communal designs can encourage inclusivity and shared identity.

Through these design elements, architecture not only reflects but also shapes power structures, influencing how we interact with and perceive the world around us.

sbb-itb-1be9014

Modern Views on Architecture and Power

Today's architects are rethinking how buildings can perpetuate inequality, shifting their focus toward using design as a tool for social justice. This transformation redefines the architect's role, moving from a position of authority to one of collaboration with the communities they serve.

Designing for Fairness in Modern Times

Modern architecture increasingly prioritizes community-driven approaches, centering local needs in every project. A great example is MASS Design Group's Butaro District Hospital in Rwanda, completed in 2011. This project was developed in close partnership with local residents, healthcare workers, and patients. The hospital incorporates natural ventilation, locally sourced volcanic rock, and breathtaking views of the surrounding landscape. Beyond its design, the project reinvested 85% of its construction costs back into the local economy, generating jobs and fostering economic growth.

In Chile, ELEMENTAL's Quinta Monroy Housing project introduced a creative solution: "half-houses" that families could expand as their finances allowed. This approach gave residents the opportunity to shape their living spaces over time. Similarly, Urban Think Tank's Empower Shack project in South Africa used participatory design to create affordable, expandable housing tailored to low-income families' practical needs.

These projects reflect a broader movement in architecture - designing with communities rather than for them. Brian Price, chair of the graduate architecture program at California College of the Arts, captures this sentiment:

"Architecture, at its root, shapes lives. It has real social repercussions, so it must be inclusive."

Architects are also challenging traditional building regulations, experimenting with new financing models, and crafting creative solutions that prioritize community well-being over developer profits. For instance, in London, where tenants spend an average of 49% of their pre-tax income on rent, firms like Karakusevic Carson Architects are involving residents directly in the design process to develop thoughtful, community-centered social housing.

These efforts underscore a key principle: architecture must address the needs of the communities it serves, a value that lies at the heart of contemporary architectural ethics.

The Ethics and Responsibilities of Architects

The architectural field is increasingly acknowledging how design choices influence social equity. Where people live often determines their health and opportunities.

Yasmeen Lari's post-disaster reconstruction work in Pakistan is a powerful example of architects responding to urgent social challenges. In just eight days, she led the construction of 270 flood-resistant, low-cost homes. These homes were built using sustainable, locally sourced materials and relied on collaboration with local experts.

Modern architectural ethics are rooted in several key principles: engaging meaningfully with communities, promoting economic justice through local hiring and sourcing, adopting sustainable practices, and ensuring accessibility through universal design. This ethical shift pushes back against traditional power dynamics in architecture.

"As designers, we need to be agents of change. Architects and interior designers can play a part in shaping both the spaces and the policies of the built environment. We can leverage our skills toward environmental, political, and social justice", says Antje Steinmuller, chair of the undergraduate architecture program at California College of the Arts.

The profession is also grappling with its historical role in perpetuating inequality. Whitney M. Young Jr. famously said, "Architects share the responsibility for the mess we are in ... this didn't just happen. We didn't just suddenly get in this situation. It was carefully planned". This recognition has fueled efforts to rectify past injustices, focusing on inclusive revitalization that avoids displacing existing residents.

As ethical practices evolve, digital tools are emerging to support this more equitable approach.

How Architecture Helper Supports Inclusive Design

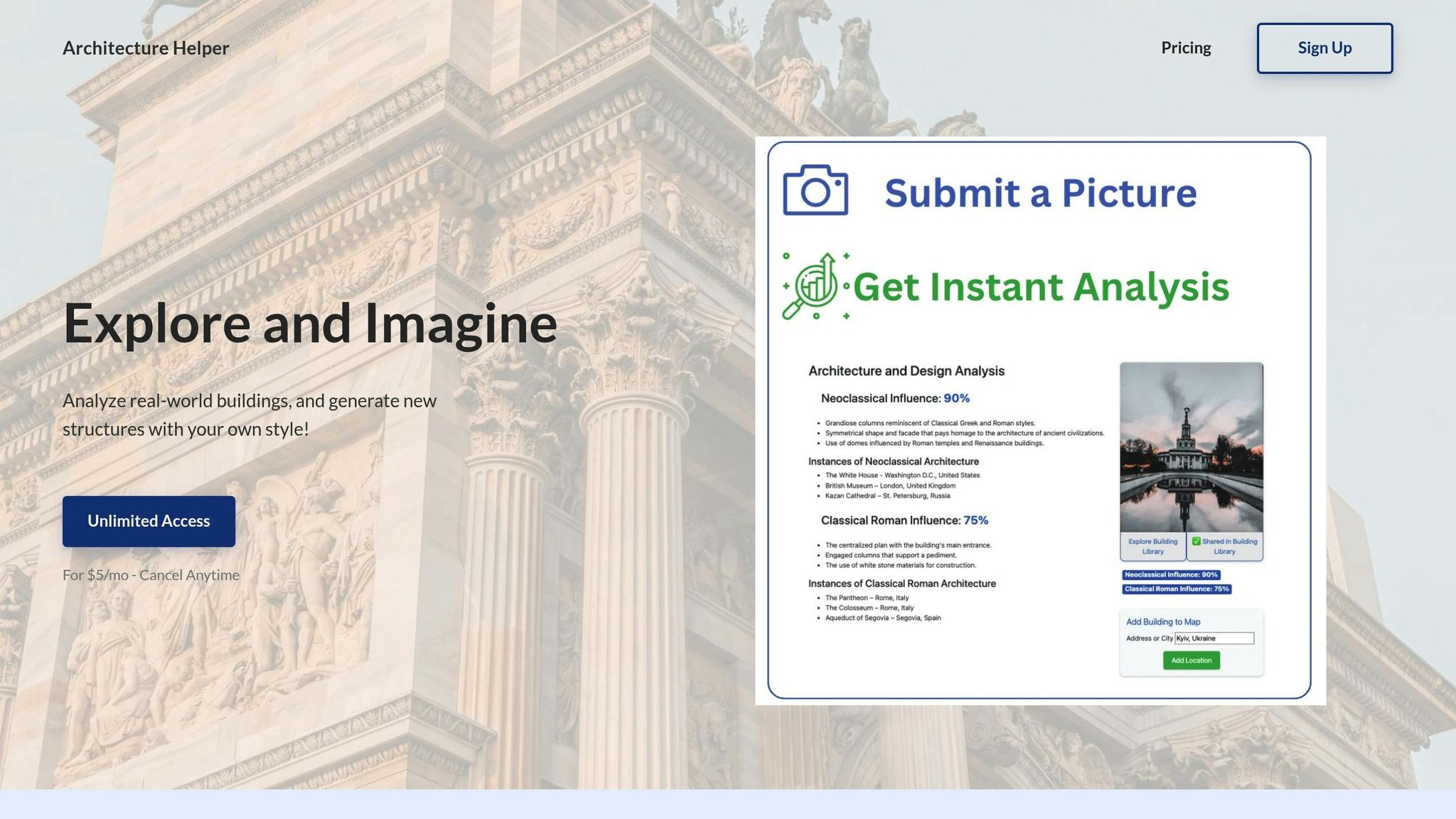

Architecture Helper is a digital platform that makes architectural analysis accessible to everyone. Users can upload photos to receive instant insights into architectural styles and historical influences, helping them understand how design elements convey authority, wealth, and community values.

The platform also allows users to experiment with design by combining different architectural elements. This hands-on feature encourages creativity and helps users see how design choices impact a building's function and message.

By offering educational resources and user-friendly tools, Architecture Helper breaks down barriers in the field. It democratizes architectural knowledge, ensuring that more people - especially those from underrepresented communities - can engage with and preserve their local architectural heritage. This aligns with the broader goal of using design to empower communities.

"Architecture and interior design can imagine and create alternative futures", says Amy Campos, chair of the interior design program at California College of the Arts.

As architecture continues to move toward more equitable practices, tools like Architecture Helper play a vital role in shaping environments that serve everyone, not just a privileged few.

Conclusion

Power and Architecture Through History

Architecture has always been a powerful tool for expressing authority. Think of the Great Pyramid of Giza or the Palace of Versailles - each structure was designed not just to impress but to assert dominance and a ruler's connection to the divine.

Take the Colosseum in Rome as another example. Its massive scale and the public spectacles it hosted were clear demonstrations of imperial strength. Similarly, the Ziggurat of Ur, with its base spanning 64 by 46 meters and standing 12 meters tall, symbolized the Mesopotamian rulers' unique role as intermediaries between gods and humanity.

"Throughout history, architecture has been a potent symbol of power, serving not only as a reflection of a ruler's ambition but also as a testament to the strength and influence of entire empires." - John Valentine

Today, the focus of architecture is shifting. Instead of building monuments that project dominance, many modern architects are prioritizing designs that empower and serve communities.

Shaping the Future of Architecture

Learning from history, architects are reimagining how power is represented in design. The emphasis is shifting toward equitable, sustainable practices. Digital tools are breaking down barriers, making architectural knowledge more accessible. For instance, platforms like Architecture Helper let users explore how design elements influence social messages, fostering a deeper understanding of architecture's role in society.

Sustainability is no longer optional - it’s becoming standard. Architects are embracing climate-conscious techniques like passive solar design and regenerative principles. Tools such as BIM, AI, and parametric design are revolutionizing how projects are conceived and executed. Urban planning is also evolving, with concepts like the "15-minute city" prioritizing walkability and community access.

Material choices are another area of transformation. Architects are considering the ethical and social impact of materials from the very beginning, using them as a means to promote social justice. Human-centered design is gaining traction, encouraging sensitivity to neurodiversity, mental health, and cultural nuances in every decision.

The role of architects is expanding. Beyond designing buildings, they are becoming educators, sustainability advisors, and community advocates. This new approach recognizes that design is never neutral - it can be a force for fairness, generosity, and justice when approached thoughtfully.

As architecture continues to evolve, the lessons of the past remain vital. By understanding how spaces have been used to exclude or intimidate, today’s architects have the opportunity to create environments that are inclusive and empowering - ensuring that the benefits of thoughtful design are shared by all.

FAQs

How does architecture shape social power in modern urban planning?

Architecture holds a powerful influence over social dynamics within urban planning. It shapes how people connect with their surroundings and interact with one another. Public spaces, streets, and buildings that are thoughtfully designed can create opportunities for inclusivity, encourage active community participation, and help support social equity.

However, architecture can also mirror or even reinforce existing power structures. For instance, exclusive designs or spaces that are difficult to access can maintain social hierarchies, while more inclusive, participatory approaches can work to challenge these norms. In this way, architecture not only reflects societal values but also serves as a tool to reshape how power is shared and experienced in urban environments.

How are historical architectural styles used in modern buildings to reflect cultural heritage and social influence?

Modern Architecture and Historical Styles

Modern architecture frequently weaves in elements of historical design to pay tribute to heritage and reflect societal values. For example, contemporary buildings might showcase Islamic geometric patterns, Gothic arches, or classical columns, drawing on these timeless styles to evoke a sense of tradition and permanence. These choices do more than just nod to history - they celebrate cultural identity and convey a sense of authority and importance.

By merging traditional aesthetics with modern functionality, architects create spaces that bridge the gap between the past and the present. This thoughtful blending not only instills cultural pride but also keeps historical influences alive and relevant in today’s world of design.

How are architects today incorporating social justice and equity into their designs?

Architects are increasingly emphasizing social justice and equity by designing spaces that are welcoming, accessible, and centered around the needs of the community. Their work goes beyond aesthetics, aiming to create environments where diversity thrives and everyone feels they belong.

Some of the key initiatives include:

- Affordable housing: Tackling housing inequality by designing homes that are both cost-effective and high-quality.

- Universal design: Ensuring buildings and public spaces are accessible to individuals of all abilities.

- Cultural sensitivity: Incorporating local traditions and values into urban planning to honor and reflect the diversity of communities.

These efforts are transforming architecture into a means of social renewal and restorative justice, shaping spaces that empower and uplift communities while fostering equality.